Since this week we’re focusing on the habit of proper praise, I’m thinking about my stubborn teenagers. Each of them in his own way has managed to get under my skin over the years, and I haven’t handled it well. I’ve come to realize this is because I’ve harbored the notion that I’m entitled to a disturbance-free life.

You can see how children might undermine one’s desire for calm. Far too late into fatherhood, I realized how often I get irritated at my kids for being, well, kids. Worse, as I’ve learned about the habit of praise, I’ve come to realize how often I got (and still get) irritated at them for manifesting traits which are good.

Qualities like honesty, persistence, and intensity can be challenging when they begin to bud. Thank God they’re hard to squash, though I wonder how many children this world manages to mangle permanently, what with our widespread desire for easy parenting, the prevalence of mind-numbing entertainment, and schools geared for somnolent obedience over the cultivation of virtue and action.

Since I’m also learning that the path to world reform begins with yourself, what all this big talk means in practice is that I’ve had to work on catching myself when irritation sets in, and asking whether the irritating thing my child is doing comes at least in part from a good place.

I’m realizing, further, that I should ask this about anyone’s actions, especially my own. Too much of my behavior-management has been superficial, aimed at the leaves rather than the roots.

My 15 year-old, for example, has an uncanny ability to sniff out hypocrisy. Once, when I complained about a jerky driver in front of us, he noted three or four jerky things I had recently done as a driver. My first instinct was to slow my truck to a less lethal speed and push him out the window. But the kid was right.

When he was four, my now 18 year-old insisted on riding a bike, repeatedly launching himself down the driveway and crashing. I pleaded with the boy, as his knees slowly turned to hamburger, to just use a bike with training wheels. But no, it was essential to him for some reason to ride a big-boy bike.

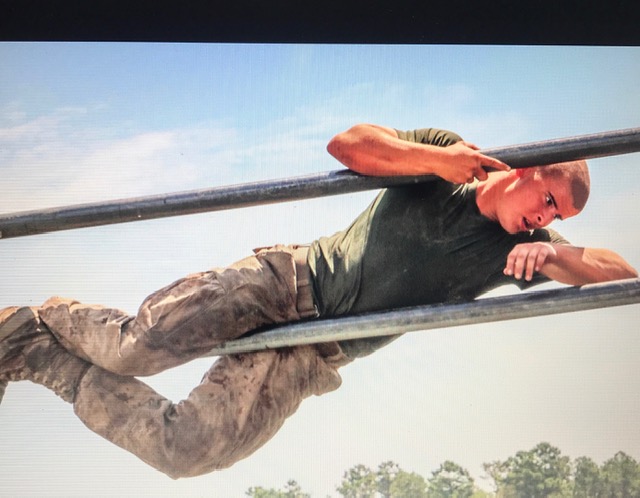

My 20 year-old, meanwhile, has always been like a hunting dog with a scent. Once he locks in, there’s no distracting him. No reminding him that there are other things he should be doing. No suggesting that perhaps his obsession with learning how to build a computer, or training like a Navy SEAL, or building a survivalist go-bag is, perhaps, overdoing things a bit. He always seemed to have just two gears: Disinterest and Overdrive.

Not only have they irritated me, these boys have produced a fair share of chaos, epic messes, broken bones, and poor grades in subjects that bore them. I’ve worried whether each of them would survive childhood, and whether I would survive them.

Now I’m seeing how many of those irritating qualities sprang from strengths that are the best parts of them. Thank God they’ve been more persistent in becoming men than this man has been in conforming them to his desire for comfort.