When I’m gone more than a couple of days, the youngest human being in the house tries to take charge. He’s seven years old—younger by minutes than even his twin. Call him Jackrabbit.

Brief digression: A few years back I started writing a book about parenthood, faith, the best way to plant potatoes, and the like. I gave my kids codenames to afford them a bit of anonymity. The names I chose were whimsical and, in retrospect, perhaps a bit silly. The thing is, much of that manuscript is in longhand, which makes changing the codenames a challenge. As several partially finished manuscripts and a shed full of non-functioning machinery can attest, any work that lands on my list must bide its time. And two sets of codenames for my kids would just be, well, weird.

So, Jackrabbit. The little alpha bear. Where his twin brother (Professor) is cerebral and calm, Jackrabbit is a man of action. The actions he takes, in my absence, are things he sees me doing when I’m home. He climbs onto the kitchen counter and stretches the sink hose to our Berkey filter when it needs refilling. He sits in my chair and tries to do my New Yorker crosswords. He tells his mother how things are going to be around here.

(I don’t know where he gets that from; being a man who doesn’t want to wake up dead some morning, I am not in the habit of bossing Jackrabbit’s mother around.)

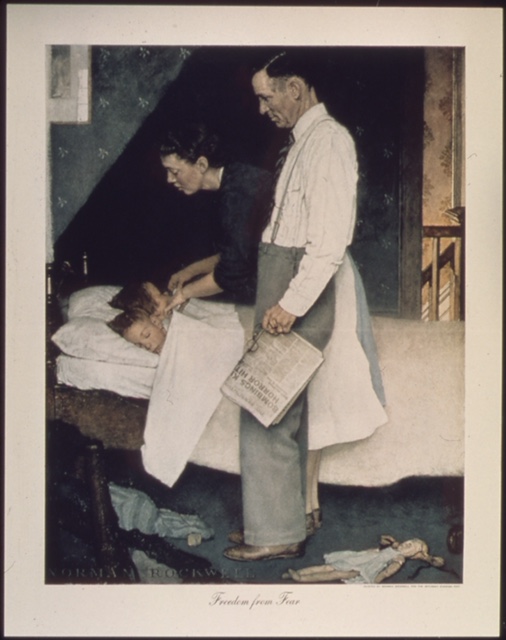

I read somewhere that children stay closer to their teachers when their schoolyards don’t have fences. Put in a fence, and the kids roam farther. Perhaps paradoxically, boundaries make children feel safe to explore. That seems to be physically true, and perhaps metaphorically as well. We’ve all met kids whose parents don’t set boundaries—for their children or themselves. Sometimes the kids are withdrawn. Other times they act out, as if to provoke a bit of fence-building. Because if your parents aren’t in charge, how can they protect you from what’s out there?

In my absence, Jackrabbit has concluded that fence maintenance falls to him. My return often evokes a transfer-of-authority crisis. Fortunately, these crises are easily remedied with living-room wrestling. Professor will join in, usually with a leap-from-the-turnbuckle sneak attack (said turnbuckle being a couch or chair or any other elevated space that gives him a clear shot at his old man’s back). We roll about the floor, growling, until the proper order of dominance is re-established.

I don’t know what will happen when I can no longer take them—as a pair or even individually—in a fair fight. Fight unfairly, I guess. But one day it’ll be them keeping fences—same as for your children. I hope we’re teaching them how.