My 15 year-old son heard about George Floyd’s killing and found it online and watched it. Afterward he came to me and asked why it happened. Why that police officer knelt on his neck while he begged, while he called for his mama, stayed there even after he stopped moving. “Are they allowed to do that to somebody?” he asked.

I told him I don’t know the rules in Minneapolis, but that we should ask not whether something is allowed, but whether it’s right.

“That wasn’t right,” he said.

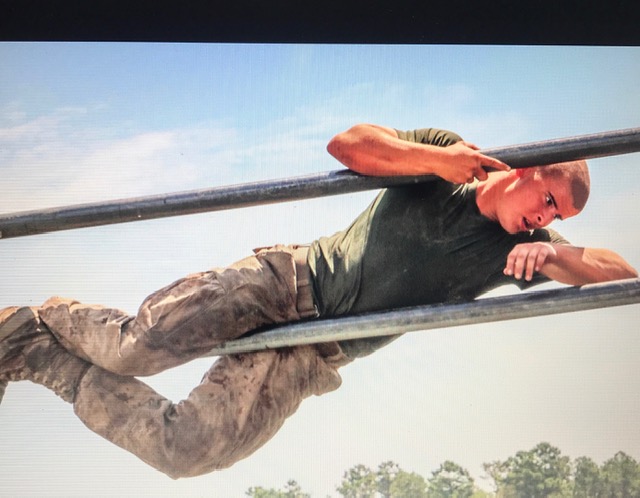

Being wrestlers, we agreed a man ought to know how to control another man who’s handcuffed without kneeling on his neck for nine minutes. We agreed a man ought not be indifferent to another man calling for his mama.

Watching that killing, and seeing the subsequent violence—a man guarding his store beaten until he’s trembling in a pool of blood, a 77 year-old retired police chief shot dead trying to dissuade looters—all I can think is: Where were your fathers? Was no one there to teach you that a man doesn’t punish the innocent for the crimes of the guilty? That he doesn’t steal in the name of justice? That he has mercy when a man says he can’t breathe?

I suspect in too many cases we already know the answer: There was no father worth a damn to teach them anything.

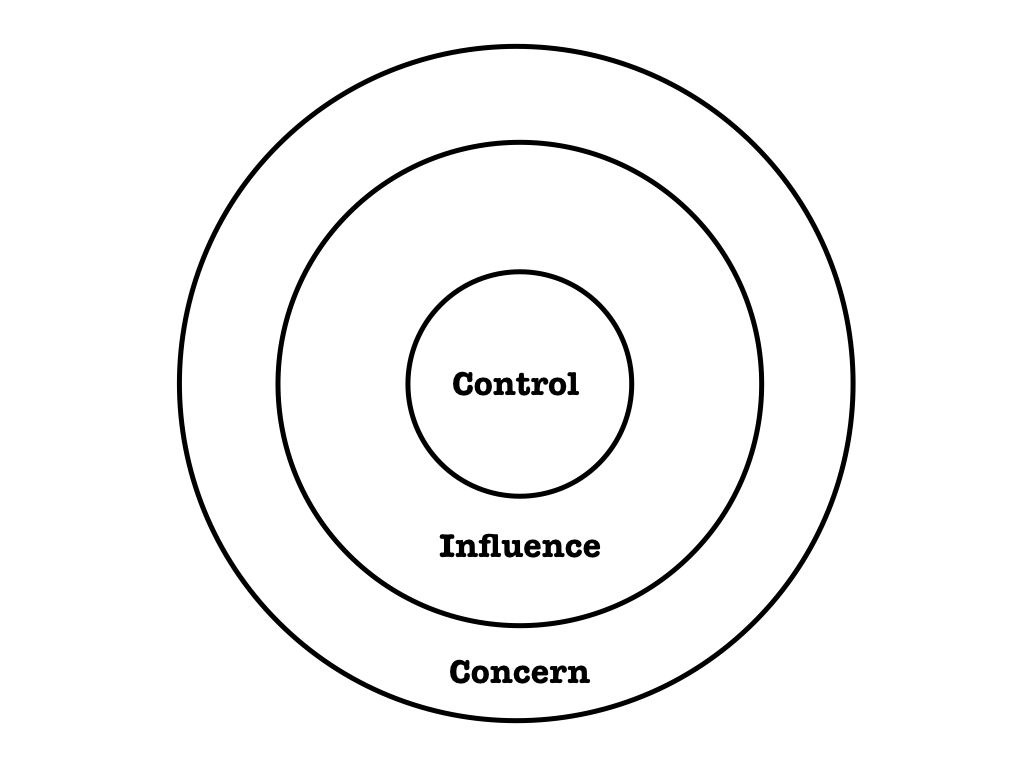

Now people rush in with plans to change the world, to fix the system, to correct the hearts of men. I used to have all those answers myself, but somehow I’ve gotten dumber as I’ve aged. I don’t have all the answers I used to have.

All I know is that my world-changing work begins right here, in this father’s heart. As it does in yours. We can’t raise our children to seek justice and give mercy if our own hearts are turned inward. The world is tormented by men with closed hearts.

So be intentional today, fathers. Be open-hearted toward your children. This is our world-changing work, and though any day’s portion may seem small and insignificant, it’s the most important work we’ll ever do.

If you doubt that, just look at what happens when fathers don’t teach their children to choose what’s right over what’s allowed: People die. Cities burn. All while our children are watching.